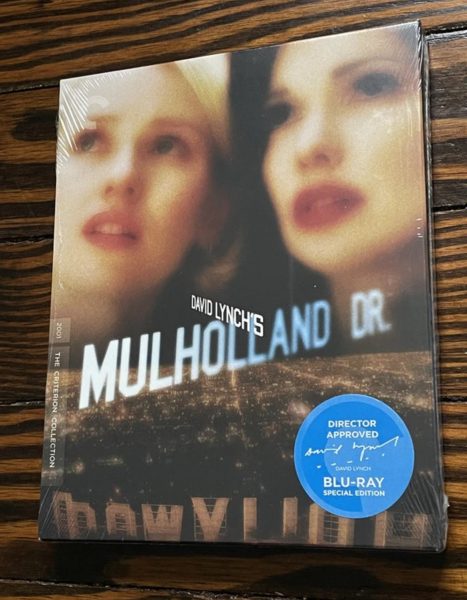

The past two decades have been marked by the rise of online streaming services for movies and music, and as a result, physical copies of media such as CDs and Blu-Ray DVDs have seemingly become obsolete. However, that can not be further from the truth.

Movies in particular never find a permanent home on these streaming services. With the transfer and subsequent acquisitions of different IPs (Intellectual Property) and streaming rights to franchises, any content involved in these deals is subject to frequent switches in their platforms; the Jurassic Park franchise has been a frequent victim of this, making its rounds on Hulu, Netflix, and HBO Max respectively for only months at a time on each service.

As a result of these frequent shifts in locations, access to a physical copy such as a DVD is one of the few reliable methods to be able to watch a movie on your terms without going through the hassle of finding out where to watch it. With a DVD, it is as simple as acquiring a copy and inserting it into its respective player to watch at your leisure.

The upfront cost of physical media can be a deterrent to possible collectors, and the problem is understandable. In my experience, used movies typically run at $6 per copy, meaning that a bundle of three used movies can exceed what you typically pay for in a monthly streaming service charge.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the average consumer does not only pay for a single streaming service. Think of the number of streaming services you use every week, it is more than likely that the number exceeds one. The true cost of all of these services can greatly exceed what you perceive them as costing when you accumulate the costs of all of these services together.

While that cumulative cost may not exceed the price you would pay for a group of DVDs of movies that you are interested in, the value in the physical copies comes from being able to truly own your access to that movie; it cannot be taken away on a whim because a separate service bought its rights.

Another perk of owning physical media is that it can contain content that is not readily available digitally. Not all artists or directors upload, or give the rights to upload, their work online. This comes into play particularly with music, as some older and smaller musical artists may not have enough of a substantial listening demand to go through the effort of uploading their music digitally.

The English band Panchiko is a clear example of this, their album D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L was released in 2000 and received little fanfare at the time of its release. It was not until a forum user posted their story of finding a CD of the album at an Oxfam store in Nottingham online that a cult following for the band developed, leading to the original members coming out 20 years after the initial release to republish the album on Spotify.

For 20 years, D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L was only available through a small-scale physical release and non-existent online. But because of its CD being found and spread online, the band was able to resurface and even make a return to music with a new album that is releasing this year in April. Their story shows how physical media can also galvanize interest in projects that were once long dead in terms of interest.

Physical media has not become obsolete in the modern age of streaming services; it has become even more important to own as a result of service flip-flopping and the access it provides to smaller artists.